Surf Break Breakdown: The Different Types of Waves You Should Know

Big waves, small waves, hollow waves, mushy waves, smooth waves, crumbly waves… no two waves are exactly the same, and that’s what makes surfing so challenging (and exciting!).

A lot of variables are involved in the physics of how a wave forms: swell intervals and intensity, wind knots and what direction the wind is blowing, tides, bathymetry (the depth and shape of the ocean floor), and—what I’ll be going over in this guide—what lurks beneath the ocean surface.

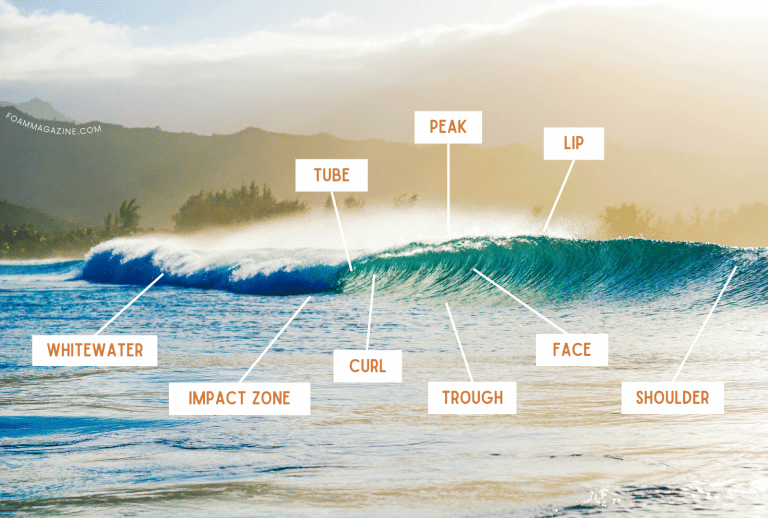

How do waves break?

Though it sometimes seems like waves just break however they want, their behavior is fairly predictable.

The individual topography of any given surf spot will affect how the waves break, and these waves can be categorized into four common types: spilling waves, surging waves, plunging waves, and collapsing waves.

Did you know? There’s another, less common and non-standard type of wave pattern called square waves (or cross waves), which are the result of two different swells coming together at a perpendicular angle.

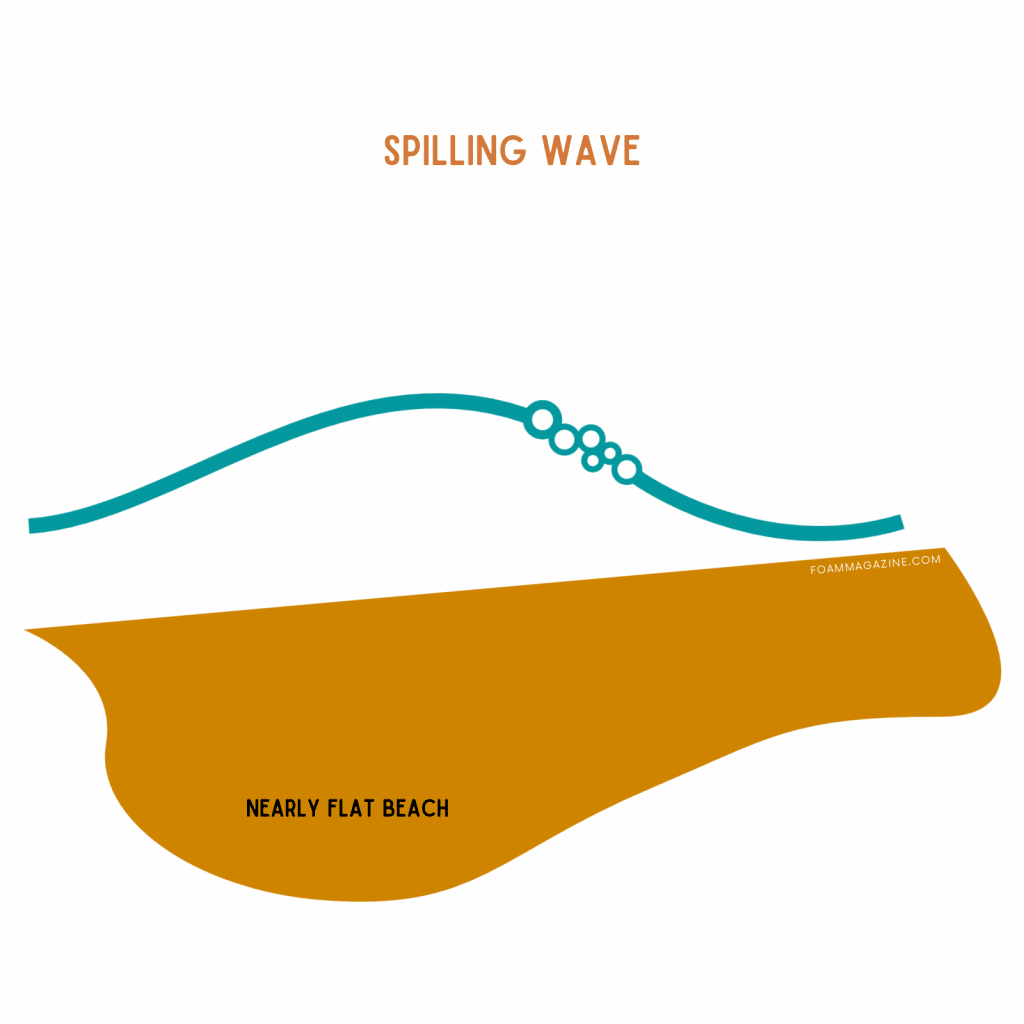

Spilling waves

Spilling waves are waves caused by a gently sloping seafloor. As the wave approaches the shore, it slowly releases energy and the crest (the top of the wave) gradually “spills” down the wave face until it all becomes whitewater.

Because spilling waves are pretty sluggish or sloppy in how they break, they’re also known as “mushy” waves.

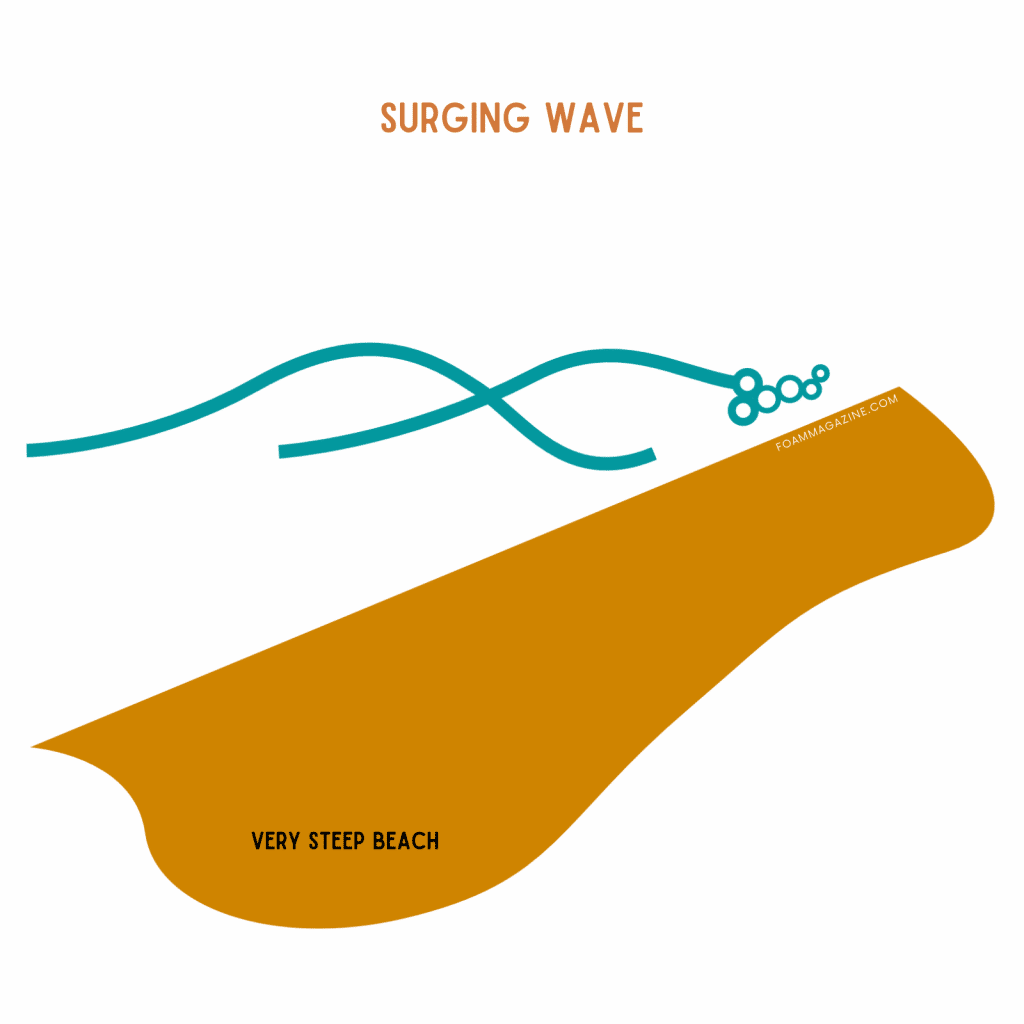

Surging waves

Surging waves are produced when long period swells come in from relatively deep water onto coastlines with steep beaches. The slow speed means there’s no time for a crest to form before the wave hits the beach. As a result, the wave surges up the beach rather than breaking, with very little whitewater.

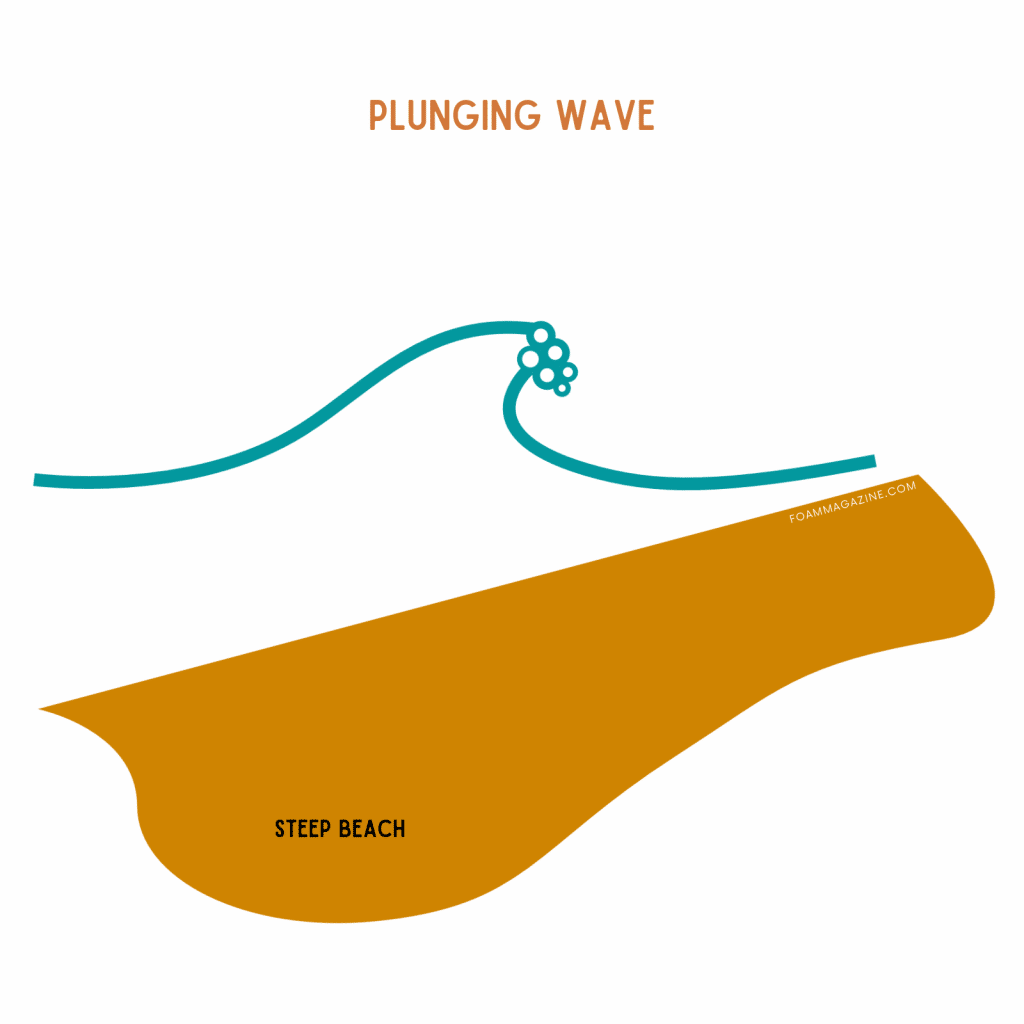

Plunging waves

Plunging waves are formed when the incoming swell hits a steep seafloor or a sea bottom with sudden depth changes—going from very deep to very shallow, such as from open ocean to a reef. This obstructs the wave’s forward momentum and as a result, the crest jacks up, curls over, and explodes on the trough.

Plunging waves are the best kind of waves for surfing!

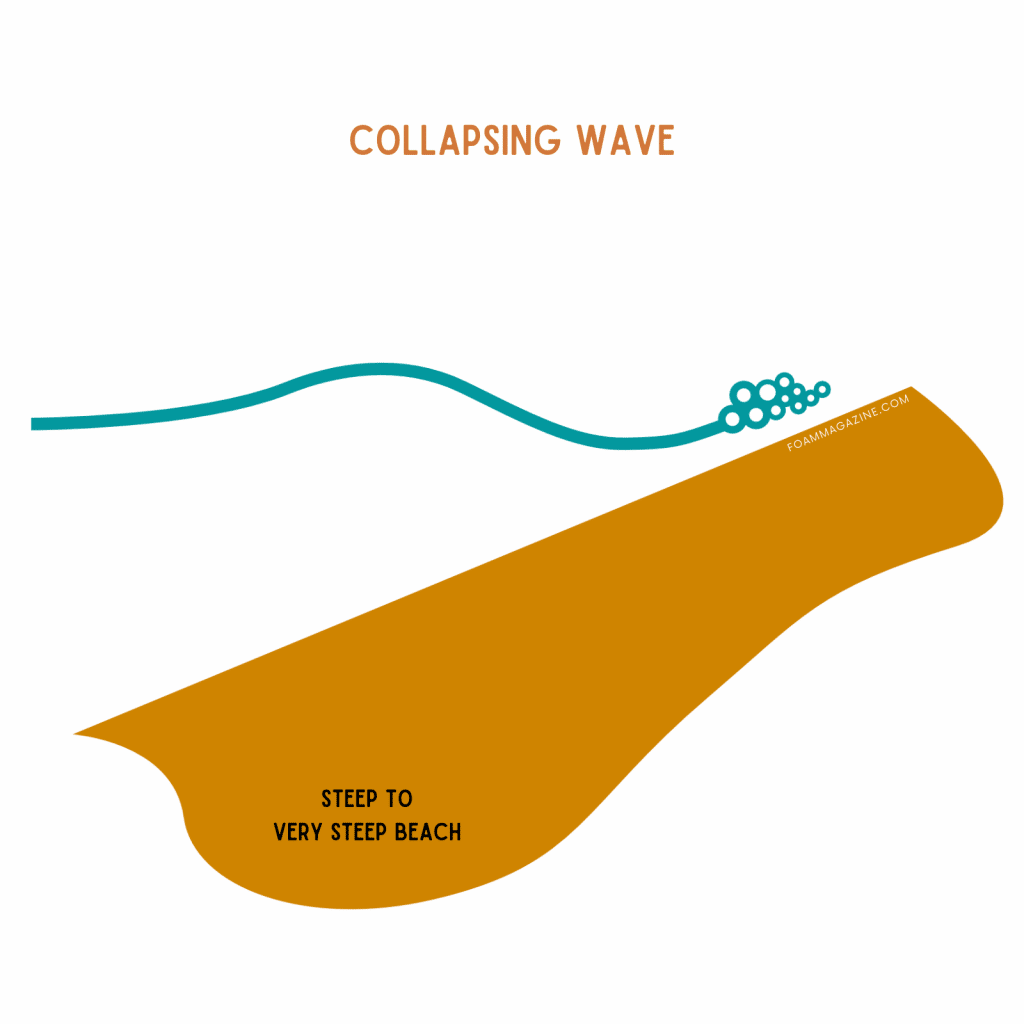

Collapsing waves

Collapsing waves are a hybrid of surging and plunging waves. The crest never completely breaks and the wave collapses, resulting in whitewater.

Other types of waves

Beyond the four main types of waves above that you’ll encounter, you’ll sometimes hear waves described as crumbly, reform, or double-up waves. Here’s how to tell them apart.

Crumbly waves

Also known as mushy waves, crumbly waves break gently and are not too fast, steep, or hollow. They’re created when the bottom contour of the seabed slopes more gradually—technically, these are called spilling waves.

Because of their lack of power, crumbly waves are forgiving, and are often ideal for beginners or surfers who want to practice new tricks without too many consequences. They’re also found everywhere, so you’re more likely to encounter crumbly waves than perfectly formed plunging waves on an average day.

Reform waves

Reform waves die down when they hit deep water, then rise and break again (“reform”) due to changes in bathymetry. They’re rather unpredictable, but very surfable.

Oftentimes, it means two different surfers can catch the same wave: A more experienced surfer may ride it and kick out before the wave hits deeper water, leaving the reform wave to a beginner who’s waiting on the inside. Or, you can pump the outside wave through the reform and into the inside shore break, giving you a two-for-one special!

Double-up waves

Double-up waves are created when two waves meet and their crests and troughs align. As a result of the wave energy from the combined waves, you get a very large and powerful wave that becomes super hollow when it begins to break. This beast of a wave is an adrenaline-filled ride for experienced surfers only!

Types of surf breaks

Remember when I said most waves are fairly predictable in how they break? That’s because their shape, behavior, and consistency is determined by the surf break.

A surf break is a permanent (or semi-permanent) obstruction in the seabed that causes a wave to break in various ways, resulting in spilling, surging, plunging, or collapsing waves. Surf breaks may be naturally formed (from sand, coral, rocks, or a headland) or manmade (from a submerged wreck or a jetty, for instance).

Understanding how a surf break works will help you read waves better.

Reef break

A reef break has anything from a smooth rocky bottom to razor-sharp coral reef under the breaking waves. That means the topography of the seabed is permanent, and the takeoff spot shifts solely in response to the size and direction of the swell. There’s usually a clearly defined, consistent channel where waves won’t break, allowing you to paddle out easily.

While reef breaks can produce perfect, almost machine-like waves, one after another, they’re also one of the more dangerous breaks to surf because of what lies beneath.

Coral reefs, in particular, can really end your day on a bad note if you wipe out and crash onto the shallow coral beds.

Rocky reefs are sometimes covered in seagrass, making them a bit more forgiving if you happen to make contact, but sea urchins commonly hide out in the nooks and crannies.

Don’t let this scare you, however—reef breaks are one of my favorite types of surf breaks. Why? Because if there’s coral, it means I’m on a gorgeous tropical beach with crystal clear water, and the waves are very predictable. Many of the world’s largest and heaviest waves break on reefs, but there are plenty of user-friendly reef breaks to be found.

To minimize injury when you’re surfing a reef break, it’s best to get in the habit of wearing reef shoes, falling with your body completely flat and floating close to the surface, and never kicking off the bottom to swim back to your surfboard.

Point break

For any surfer, point breaks create some of the longest, most epic and sought-after waves you can dream of.

Think: Jeffreys Bay in South Africa (a legendary right-hander regarded as one of the most perfect waves in the world), Chicama in Peru (a left-hander that’s also the longest wave in the world at nearly 2 1/2 miles long), Pavones in Costa Rica (said to be the second longest left in the world), and Scorpion Bay in Baja Sur, Mexico (one of the longest rights in North America).

A point break is a surf break where the shoreline juts out to sea, creating a promontory or headland that the swell wraps around. Since this land mass is a fixed feature, point breaks can be very reliable under the right conditions.

Point breaks may have rock, coral, or sandy bottoms, or a combination of rock and sand or coral and sand. As the swell comes in, it bends and peels along the headland, forming very long, consistent, high-quality waves.

The waves that form off these points all break in the same direction and generally in the same spot each time, making it easy to predict when and where to catch the wave. Unfortunately, that means there’s generally only one spot to surf, so point breaks can get crowded with surfers all concentrated in the same area.

Some point breaks offer mellow, classic longboard waves (like Malibu in California) while others produce barrels and steep, powerful surf (like Skeleton Bay in Namibia).

Beach break

Your typical beach break is made up of a shallow sandy-bottomed seafloor, and the waves break on sandbars that form underwater from currents and wave action. These sandbars are dynamic and shift with different storm and swell patterns, which means beach break waves don’t always break in the same spot every time—the next day the surf break could be 100 yards down the shore!

Beach breaks are ideal for novice surfers because they’re fairly consistent. It doesn’t take much of a swell to create surfable waves on most days, giving you plenty of practice time. The waves break in multiple places so there are several take-off spots, which help spread out the crowds.

On the other hand, beach break waves don’t always break as softly as point break or reef break waves—though if you fall, you’d just fall on a soft, sandy bottom.

Because beach breaks are highly variable based on the tide, sandbars, wind, and swell direction, you might score anything from fast, punchy, hollow waves to slow, small, playful surf, all in the same day at the same break. It also means one day you might catch the best wave of your life there and the next, you’re surfing closeouts.

That’s the thing with beach breaks—they keep you on your toes!

Jetty break

Jetty breaks (sometimes called groynes) are waves that break along any type of jetty, such as a pier, breakwater, or harbor wall. These breaks often occur over a sandy bottom and the jetty can improve the surf in that area due to the effect it has on the sandbars.

An advantage of a jetty break over a typical beach break is that as the wave runs into the fixed obstruction, the water has to displace, causing the wave to pitch higher. That’s why a jetty or pier can sometimes handle larger swells before closing out and the waves are a few feet bigger than neighboring beach breaks.

Examples of jetty breaks include The Wedge in California and Long Beach in New York.

Less common surf breaks

Besides reef, point, beach, and jetty breaks, several other types of surf breaks can occur over both natural and manmade obstructions.

While they’re not as common, the waves they produce are some of the most famous waves in the world, such as the Severn Bore (a tidal bore wave in Britain that travels many miles up the River Severn, giving it the nickname of “world’s longest party wave”) and the Wavegarden (an engineered surf park with multiple locations around the world).

Rivermouth break

A rivermouth wave breaks at or near the entrance of a river or creek. The bottom is usually sand, but can also be cobblestones, rocks, or coral.

Iconic rivermouth breaks include Mundaka in Spain, Merimbula Bar in Australia, and Trestles in California.

Shipwreck break

A shipwreck break usually forms from sand that’s built up over a partially or fully submerged shipwreck. Depending on whether the wreck remains in place or how it deteriorates, this type of surf break may be temporary or more or less permanent.

A popular shipwreck break that still exists is The Wreck in Byron Bay, Australia, and past wrecks in Baja Sur, Mexico, and Nusa Lembongan, Indonesia, gave rise to their local surf breaks—each of them named, appropriately, Shipwrecks.

Tidal bore break

Tidal bore breaks are formed where strong, large ocean tides enter a river delta, allowing the tide to surge up the river and create surfable waves. Since they follow the tide cycles, tidal bore waves occur at specific times of the day, month, and year and are always predictable, oftentimes drawing large crowds of both surfers and spectators.

Besides the famed Severn Bore, there are several other tidal bore waves in the Amazon Basin in Brazil as well as Sumatra, Indonesia.

Standing river break

A standing river break occurs when a fast river flows over a natural or manmade riverbed slope just right and shapes the current into surfable waves. A surfer can ride this river wave for several minutes or more while standing more or less in the same place on the river.

Well-known standing river waves include the Zambezi River in Africa, Eisbach River in Germany, Deschutes River in Oregon, and Boise River in Idaho.

Artificial wave pool

Artificial wave pools feature powerful wave-generating machines that produce perfect, ocean-like waves in carefully controlled “surf lagoons.” These types of surf breaks can be built almost anywhere, far from any existing natural shorelines, in a range of designs and models.

Wave pools have appeared throughout history around the world, but recent developments with bigger, better wave technology include the Surf Ranch in California, Waco Surf in Texas, and Wavegardens in Europe, Asia, Australia, and South America.