All About Swells: What They Are and How They Form in the Ocean

As surfers, we refer to water in a lot of ways: ocean, sea, surf, swell, waves, not to mention the different types of waves we like to ride (lefts, rights, A-frames).

And though we tend to talk about swell and waves interchangeably, there’s a subtle difference between the two terms when it comes to the kind of surf arriving at your local beach.

What is a swell? How are the waves formed? And what are those other terms you often see in surf reports like swell height, swell period, and swell direction?

That’s exactly what I’ll be covering here, without you needing an oceanography degree to understand it all!

The difference between swell and waves

A swell is a group of waves (usually with smooth, unbroken tops) traveling across the ocean, created and energized by storm winds raging hundreds or thousands of miles out to sea. The swell has a distinguishable collective height, period, and direction.

It moves from very deep water—away from its source, such as a hurricane or other storm event—toward very shallow water near the coast.

When the swell hits a change in depth in the seabed, the type of obstruction—whether it’s a headland, reef, sandbar, jetty, or just a gentle slope—will either slow the waves down and make them spill over (forming mushy waves) or make them rise and curl over (forming steeper waves). The size and quality of these waves will depend on the local winds, tide, and surf break.

So to put it simply, swell refers to the overall event, while waves refer to the end product.

What affects the size of the swell

Waves would not exist without wind. When it comes to the waves out at sea, three main things affect their size:

- Wind speed: The greater the wind speed, the larger the wave.

- Wind duration: The longer the wind blows, the larger the wave.

- Fetch: The greater the distance the wind travels over open water, the larger the wave.

When it comes to the waves at a certain surf break, their size is impacted by various factors including:

- Swell direction: Is the surf break exposed to the current swell direction?

- Bathymetry: What does the depth and contour of the seafloor look like?

- Tide: Some surfs spots only work on certain tides.

How swells are formed

All swells are formed by wind blowing over the surface of the ocean.

But these are not the breezes you experience onshore; swell winds are generated by severe storms (such as hurricanes, cyclones, and typhoons) that take place in the open ocean, thousands of miles away from any landmass. (This is why the majority of powerful swells happen during winter.)

Think of this storm event like a pebble dropped into a pond, sending out ripples of energy in concentric circles. The stronger and longer the wind blows, the larger the ripples become.

At first the waves will just be a small surface chop, but as the winds continue to blow, the waves get bigger and deeper. Their size is dependent on the speed of the wind blowing behind them, since certain wind speeds will only be able to generate certain wave sizes. Once the largest waves that can be generated for a given wind speed have formed, the seas are “fully formed.”

As the winds continue to blow very strong for a long time over massive distances, the distance between each wave (known as a wavelength) becomes longer and the energy driving the waves becomes greater.

Each group of waves will vary in speed and wave period. The longer-period waves are faster and move farther, overtaking swells with shorter wavelengths or combining with other swells to grow larger and more powerful. As they travel farther away from the original storm, they start to organize themselves into swell lines. This is how wave trains form, and they’re the “sets” you see rolling in to the coast.

Although these waves originate from adverse weather events, they’re no longer subject to those winds once they reach the coast—at this point they’re known as ground swell, the type of waves you want as a surfer!

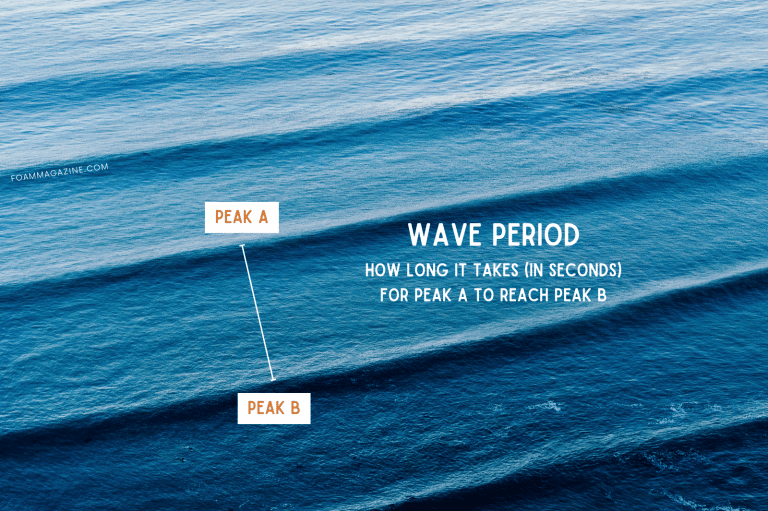

Ground swell vs. wind swell

Ocean swells can be described as either:

Groundswell, which is generated by winds far out to sea that have traveled longer distances. The waves have more energy and the swell period is longer, resulting in cleaner, more organized surf.

Windswell, which is generated by high pressure systems just off the coast. The waves come in fast with short swell periods, resulting in unorganized sets and messier waves stacked on top of each other.

Windswells don’t generate much power below sea level, so they’re less affected by the bottom of the ocean. They tend to peak up in random spots so they don’t wrap neatly around headlands and point breaks. The waves only travel so far before they lose energy.

Despite windswells being somewhat short-lived, they typically occur more frequently than groundswells and they do create waves you can surf. Beach breaks often get fun, peaky waves from windswell, which is why they’re great for crowds—there’s a little something for everyone.

Swell height, swell direction, and swell period

Remember when I said up there that an organized swell has a collective height, direction, and period? These three factors determine where you can surf a specific swell, since one beach might be going off while around the corner, the other beach is pretty much flat.

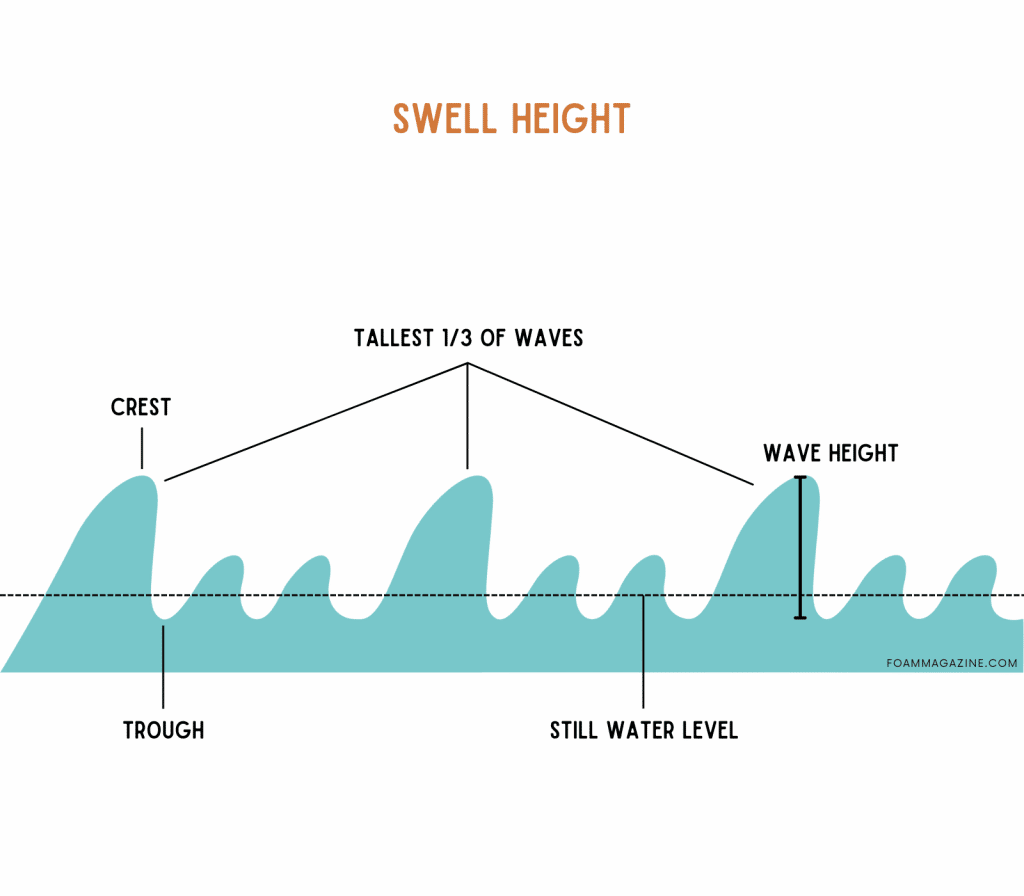

Swell height

Swell height is the average size of open-ocean waves passing a buoy in a given hour. The wave is measured from the trough (lowest point) to the crest (highest point). Forecasters generally report on the average height of the tallest one-third of the waves.

As you can imagine, however, the ocean is a busy place so there are usually primary and secondary swells being measured by the buoys, which all show up in swell charts. (I talk more about primary and secondary swells below.)

The important thing to keep in mind is that swell size is different from wave size at your local beach. That’s because when the swell travels through deep water and then hits shallow water, it’s forced upward into a larger wave (known as wave shoaling). So the little 2-foot swell on the surf report could actually produce fun, shoulder-high waves once it makes landfall.

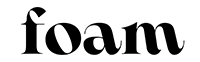

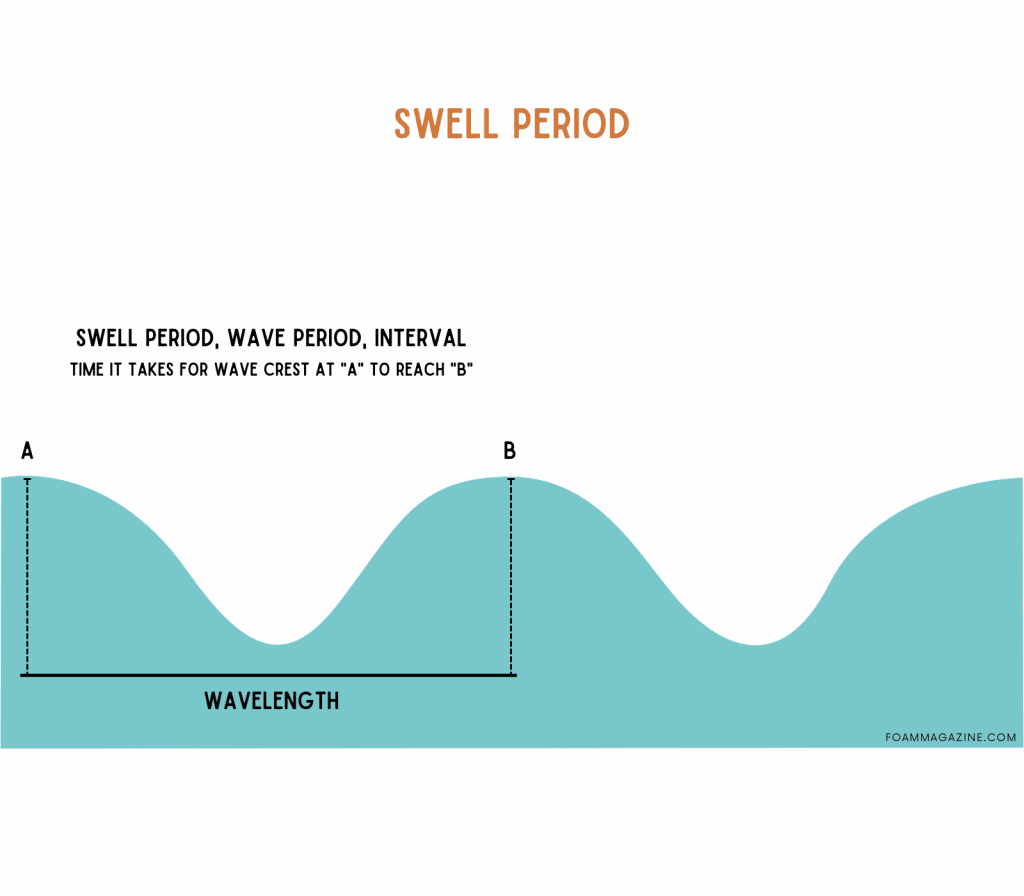

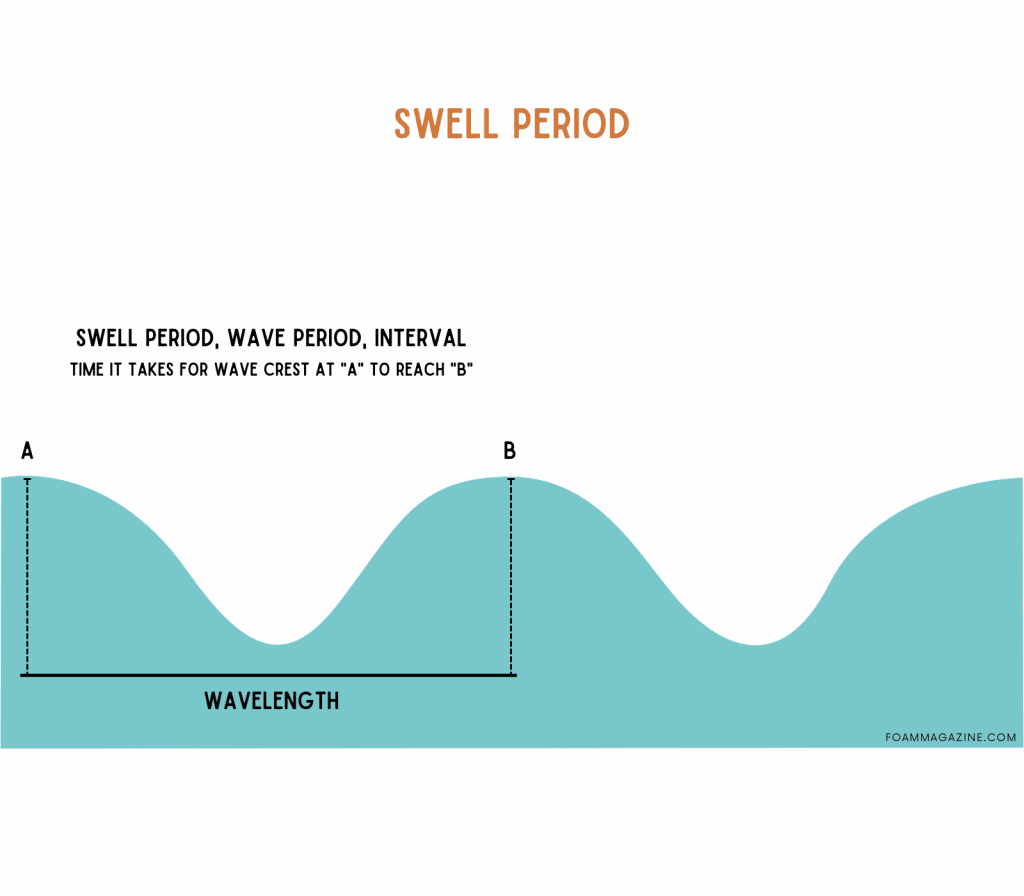

Swell period

Swell period, wave period, and interval are terms used interchangeably, and they all refer to the time it takes for successive waves to pass the same point. The amount of time is measured in seconds between the crests of the waves in a swell.

Long-period swells are typically over 12 seconds and short-period swells are anything under 10 seconds.

A longer period means a swell is traveling from farther away, has more energy, and generally has a flatter profile in the ocean, so it produces larger (but less consistent) waves when it enters shallow water.

A shorter period means the waves are weaker and smaller, though they’ll come in more consistently, giving you less-perfect but many more waves to surf.

Sometimes you’ll see a 10- to 12-second interval referred to as a mid-period swell. In this range, the swells are starting to move away from the storms that created them, so they’re not as jumbled up and peaky as windswell, but not as clean and powerful as groundswell.

Swell direction

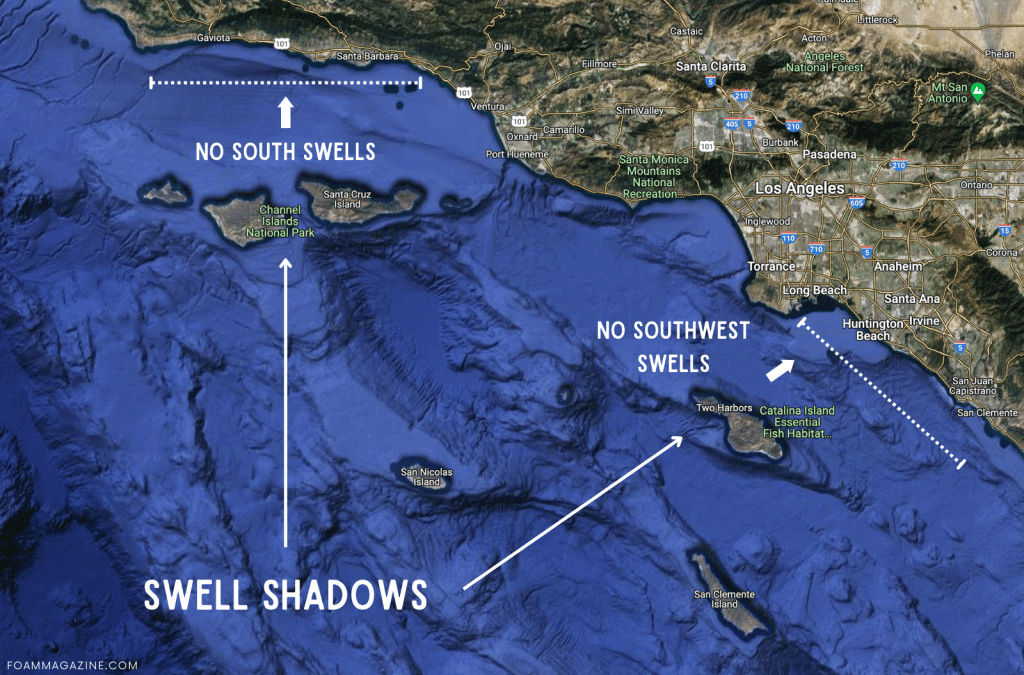

Swell direction is the direction of the swell’s origin, not the direction it’s heading. So a north swell comes from the north but is heading south, and any north-facing beaches will receive the swell.

In surf reports, swell direction is described in compass degrees, with north at 0° (or 360°), east at 90°, south at 180°, and west at 270°.

While the angle of the swell will determine how the waves will be at a specific spot on the coast, the waves might break differently at neighboring surf spots depending on the seabed contour, coastal characteristics, and what direction the surf break is facing. Even as little as 10° difference can have a significant impact at some surf spots!

If you look at a map, you can get a good sense of what swell directions a surf break is most exposed to, as well as what might be in the way of the swell, like islands or headlands. These barriers are called swell shadows, and they can radically diminish the swell size and sap its energy before it gets to the surf break.

What are primary swell and secondary swell?

Swells are categorized into primary, secondary, and tertiary swells (and there can be more swells, but they rarely influence a single surf spot at the same time). This happens when several different storms in different places out in the ocean produce swells that all arrive at a particular location.

A primary swell and secondary swell moving in the same direction toward the same surf break may combine to create a larger swell. But, typically you get a few swells in the water, each coming from a different direction and with different swell heights and swell periods. In these instances, the primary swell is the one most likely to impact the types of waves coming onshore.

Depending on the surf forecast, it might show just one combined swell estimate, or the top three to five swells.