Onshore Wind vs. Offshore Wind: What They Mean for Surfing

Like I talked about in another post about swells and how they’re formed, without wind there would be no waves. And you’ve probably heard the terms onshore winds and offshore winds thrown around, but don’t fully understand what they mean.

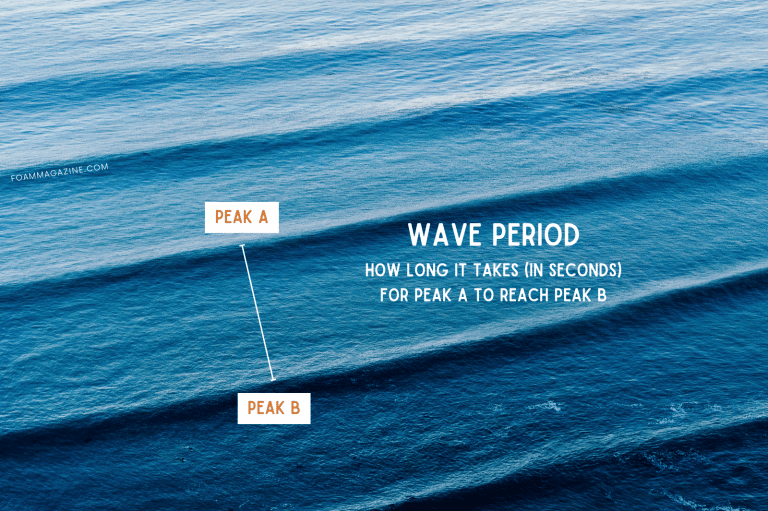

On the surface, it seems simple enough: If the wind is onshore, it’s blowing from the ocean onto the shore, and if the wind is offshore, it’s blowing from the shore toward the ocean. There’s even a type of wind that blows sideways! (That one’s called cross-shore.)

But how do these winds affect surfing, and why is one better than the other when it comes to wave quality? Here’s what you need to know the next time you paddle out.

Onshore wind

Onshore winds are the most common winds around the world and usually start mid-morning until just before dusk. This is one of the reasons surfers prefer to paddle out in the morning, or wait until the evening glass-off when the winds calm down.

Onshore winds blow from the ocean toward the shore and usually bring less than stellar surf conditions. They tend to flatten the waves and cause them to topple sooner than they would naturally, and break in deeper water, reducing the steepness of the waves and making them slower and choppier.

While the general perception is that onshore winds equate to poor surf, this isn’t always the case. The waves can still be plenty fun to ride, especially at beach breaks and sometimes even point breaks. That’s because onshore winds prevent closeouts and create peaks where none would otherwise exist.

If you’re trying to learn some aerial tricks, slight onshore winds give you more practice time on the lips, since they break more often.

This kind of wind also tends to thin out the crowds at surf spots, so more peaks means more waves for you (and fewer surfers in the lineup).

Offshore wind

Offshore winds are the most favored wind direction by surfers. This type of wind blows against your back if you’re sitting on your surfboard facing the ocean.

When you’re on the beach, you can always identify an offshore wind by how it produces a misty white spray that goes up and over the back of the breaking waves out to sea. This is a classic aesthetic seen in every iconic surf shot!

Offshore winds create some of the best surf conditions because they smooth out the waves, create steeper faces, and hold the waves up, thanks to the opposing directions of the wind and waves. This makes the waves cleaner and easier to read (not to mention surf).

However, there can sometimes be too much of a good thing. If offshore winds are too strong, they can make it harder to catch the wave. You have to use more energy to paddle as you fight against the wind to drop into the wave, all the while having water pelt you in the face. Or, if the wave is small, a strong offshore wind might result in it not breaking at all.

Cross-shore wind

So this is a term you may have heard before: cross-shore wind. Compared to the other two, cross-shore winds are probably the worst for surfing.

If a wind is cross-shore, it means it’s blowing across the beach from left to right or right to left (parallel to the shore). This has a “ruffling” effect on the ocean and the tops of the waves as they break, causing them to deform or break in strange ways.

Cross-shore winds make it harder to read the waves and may even blow you out of position if you’re sitting on your surfboard, waiting for a wave.

What kind of wind is best for surfing?

So you know that offshore winds produce the best conditions for surfing, but how strong of a wind?

Since every surf break is unique, with some having cliffs, headlands, or even a harbor that might shelter them from strong winds, this is highly variable. Sometimes it takes an offshore wind of 20mph or more to give smaller waves some size and shape, and sometimes that kind of wind can make the day more challenging.

But generally for surfing, you want light offshore winds under 15mph for clean, groomed waves.

Anything more than that (say, a gusty offshore wind over 25mph) will make it harder to paddle into waves and, on weaker swells, harder to generate speed on the waves.